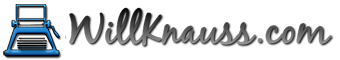

Paperback cover of the Week: Daisies in a Chain

Cute Couples Kissing

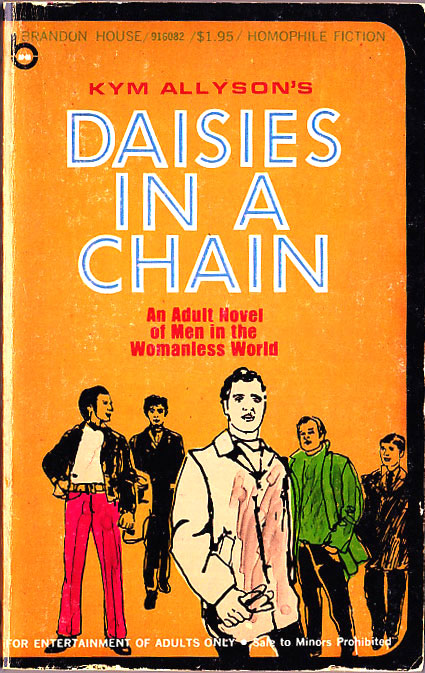

Cool Cinema Trash: The Swinger (1966)

What self-respecting Ann-Margret movie would be complete without a title song sung by the fiery chanteuse herself? The Swinger (1966) certainly doesn’t disappoint. It has a doozy. Clad entirely in skin-tight black, Margret encourages everyone to “Come on and swing with me!”

What self-respecting Ann-Margret movie would be complete without a title song sung by the fiery chanteuse herself? The Swinger (1966) certainly doesn’t disappoint. It has a doozy. Clad entirely in skin-tight black, Margret encourages everyone to “Come on and swing with me!”

What it’s all about: A bouncy instrumental version of the theme finishes out the opening credits as a high toned narrator suggests that L.A. is, “always cultural, always educational… a land of enchantment.” While he pontificates, we’re shown the seedy side of Los Angeles, run down strip clubs, XXX theatres and faded landmarks.

Our narrator is Sir Hubert Charles (Robert Coote), British lecher and publisher of Girl Lure magazine. Inside the corporate offices of Girl Lure, Sir Hubert finds his daughter in the arms of editor/playboy Ric Colby (Tony Franciosa). While they proof an upcoming layout, Ric insists that, “Even for a girlie magazine there’s such a thing as good taste.” Too bad the same rule doesn’t apply to Ann-Margret movies.

Wholesome Kelly Olsson (played by Ann-Margret whose last name is, in fact, Olssen) is mistaken for a model, plucked from a bevy of beauties in the waiting room and quickly ushered into a photo studio. “I am not a nudie,” she insists, “I’m a writer.” But they’re not interested in her stories, just her body. After watching Sir Hubert chase his secretary around his desk, an idea comes to her. “Sex, flesh, hanky-panky… that’s what they want. I know how to get published.”

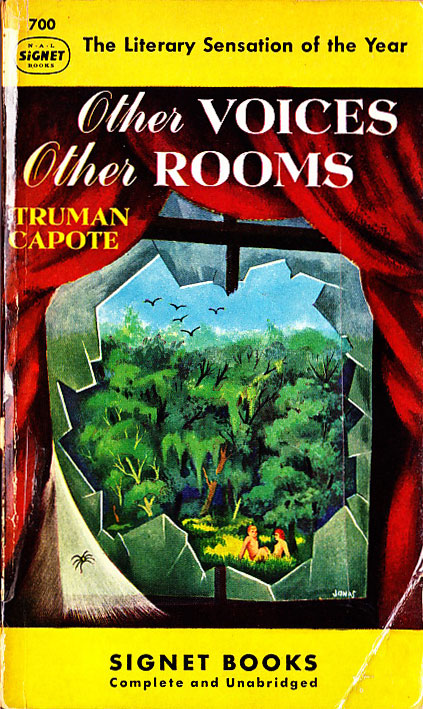

With an armload of pulp paperbacks as her guide, Kelly settles in front of her typewriter and begins to pump out prose that Girl Lure won’t be able to resist. Kelly lives in an L.A. mansion that’s home to a rollicking artists commune (where else would a young, naive mid-western writer live?). With her nose buried in her “research”, she dances from room to room as the camera lovingly follows every gyration of her curvaceous figure. As she shimmies and shakes, a gale force wind tosses her hair. Never mind that she’s indoors and there’s nary a fan in sight.

Kelly hands in her new story, but is once again rejected by the magazine. After sneaking into the men’s washroom, she demands to know why Ric won’t publish her article. He calls her a fraud, “Not a true moment in it.”

“The Swinger just happens to be my life story,” she fibs.

Sir Hubert is intrigued by the biographical possibilities “of a real live nymphet” and drags Ric to the commune to see just how depraved she really is. With the help of her beatnik pals, Kelly puts on a swinging show for the prying eyes of her prospective publishers. Wearing only a bikini and some body paint, Kelly creates a messy piece of modern art as she is rolled across an oversized canvas like a human paintbrush.

“I say, this looks positively degenerate.” Sir Hubert is suitably impressed when the vice squad breaks up the party. Ric then abducts Kelly with the intention of reforming her wicked ways.

On the drive to his aunt’s beach house, Kelly draws a parallel between their current situation and the story of “that Higgins cat, the stuffy john who made a lady out of a piece of garbage.” While musing on Pygmalion, Margret (whose character is supposedly from Minnesota) inexplicably adopts a Brooklyn accent.

Ric explains to his Aunt Cora (Nydia Westman) that if he can turn Kelly into a good girl, there won’t be anything tawdry for Sir Hubert to exploit. But Kelly doesn’t give up so easily and feigns drunkenness. Ric must wrangle her out of bed and into a cold shower. When the old letch and his snooty daughter arrive, they find them wrestling underneath the shower spray.

Kelly’s scheme seems to be going a little too well. At the offices of Girl Lure, she becomes the unwanted focus of Sir Hubert’s attention. With the touch of a button, his automated office transforms into a seductive James Bond-style den of inequity. “Sir Hubert likes a sure thing!” he shouts as he chases her around his desk.

Yes indeed, sexual harassment sure is funny! But Kelly outruns him. Despite his lascivious reputation, he admits that, “I’m the only non-scorer in the whole game.” She thoughtfully assures him that his secret is safe.

Before going on a shopping spree montage at Saks, Kelly comes clean to a surprisingly hip Aunt Cora. “I think the whole put on’s a gas!” she tells Kelly, “The only way to handle men is to keep them standing with one foot on the oil slick. Then, when they tumble, it’s in your direction. Dig?”

And tumble Ric does when Kelly fakes alcohol cravings later that evening. “It’s the monkey on my back!” she moans. After tucking her into bed, she launches into the hilariously impromptu song “I Wanna Be Loved”.

Never has alcoholism been so sexy as when Margret looks directly into the camera and croons in her breathily distinctive style. The wind machine is back, but this time it makes a little more sense since the patio door is open. Some carefully focused lighting draws attention to her scantily clad assets. Not that those assets needed any more attention.

Ric’s reaction to this seduction is to tire her out with a quick round calisthenics. “When I get tired,” she purrs, “I get stimulated, baby.” She finally manages to get him into bed for an all-night cuddle.

The next day, a private eye informs Ric that Kelly is indeed pure as the driven snow. He knows that she lied, but she doesn’t know that he knows she’s a fake. Got that? It’s at this point that the film tries to pass itself off as a comedic sex farce. The Swinger is quite funny, but for all the wrong reasons.

Ric plans to drive her to confession by photographing Kelly in embarrassing and scandalous recreations from her soon to be published sexposé, a plan that culminates in a turn on the burlesque stage. Covered from head to toe in ostrich feathers, Margret sings a rendition of “That Old Black Magic” as her costume is stripped away a la Gypsy Rose Lee. “You’ve been so wonderful about it all,” he tells her, “I’ve got a special treat in store for you.”

That “treat” turns out to be some hanky-panky at a local motel where Franciscus proves once and for all that he is completely incapable of playing comedy. He’s more creepy than comedic as he chases Margret around the room in rapid Benny Hill-style.

After all, everything is funnier when you speed it up.

Ric is carted away by the vice squad and Kelly escapes with her virtue intact. She arrives home to find her parents visiting from St. Paul. Director George Sidney tries to liven up the following exchange with lots of close-ups and quick cuts. “It’s just so terrible the things I’ve done,” Kelly confesses to her mother, “I was a card dealer in a gambling den and then a stripper and a street walker… then in that motel room a man tried to forcibly seduce me.”

Mom is nonplussed. “If you think these things are bad, wait till your children grow up.” When Kelly sees Ric on a live TV report, she hops on a motorbike and speeds off to police headquarters. Ric, meanwhile, steals a squad car and speeds off to be with Kelly.

Sir Hubert chimes in with some more narration. “Will they marry and live happily ever after? Or will they destroy themselves on America’s dangerous highways?” The answer turns out to be the latter. Ric and Kelly finally meet… in a head-on collision!

“Is that any way to end a tender, delicate love story?” Sir Huber asks.

Tender? Delicate? Exactly which movie has he been watching? The film literally rewinds itself and our lovers uncrash. The finale plays out again (this time without the highway fatalities) and our lovers rush into each other’s arms. With an ending like that, the only thing left is for Ann-Margret to reprise the film’s zany theme while sitting on a… you guessed it, a swing.

In conclusion: One of the reasons The Swinger is such an adorably awful piece of cinema trash is that it tries so very hard to be “hip” and fails at nearly every turn. During the 1960’s, Hollywood was woefully behind the times. The counter-culture youth movement left Hollywood filmmakers clueless as to what the American public wanted to see. Old guard director George Sidney (who worked with Ann-Margret on Bye, Bye Birdie, 1963 and Viva Las Vegas, 1964) seems at a total loss with the material in The Swinger.

Ann-Margret was at her sex kitten peak in 1966 and The Swinger takes full advantage of that. She looks and sounds sensational despite the dubious material. But the question remains, is it believable to have a sizzling Ann-Margret playing a naive and innocent anything, let alone a naive and innocent magazine writer?

With its crazy costumes, wacky musical interludes and faux bohemian concepts, The Swinger is a star vehicle that features everything a bad movie aficionado could ask for. When Ann-Margret is added to the mix, well, that’s when a movie like The Swinger truly becomes a slice of bad movie heaven.

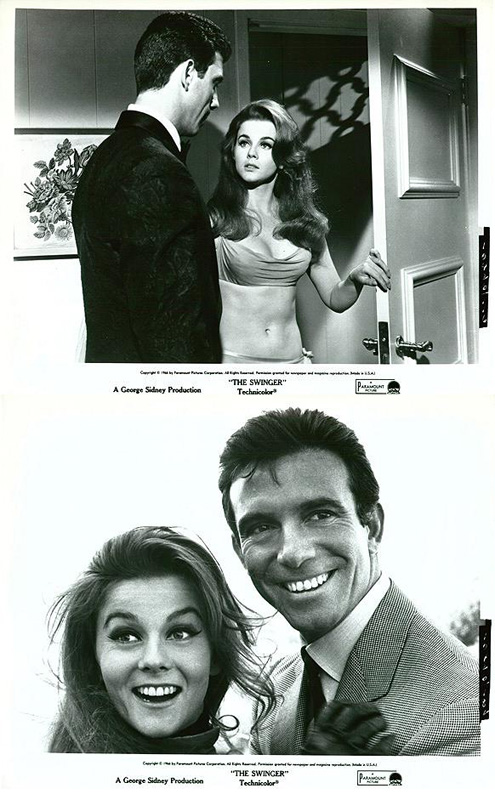

Paperback Cover of the Week: The Sergeant

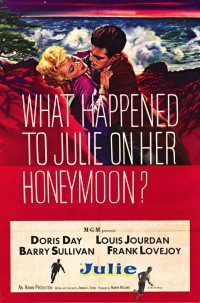

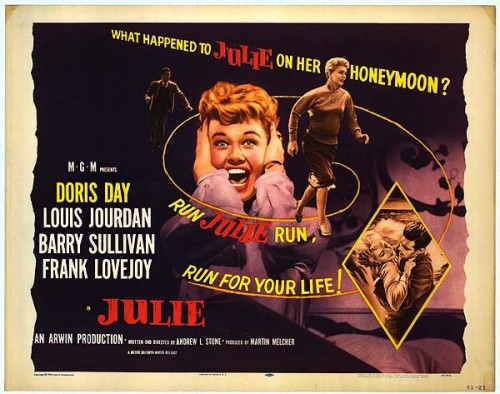

Cool Cinema Trash: Julie (1956)

What happened to Julie on her honeymoon? Run, Julie, run! Run for your life!

In the late 1950’s, Doris Day, America’s singing sweetheart, branched out from the romantic comedy genre with a handful of thrillers such as The Man Who Knew Too Much (1956), Midnight Lace (1960) and the damsel-in-distress film Julie (1956), a laugh out loud, high-flying, bad movie classic.

What it’s all about: Julie begins as most Doris Day movies do, with a sappy title song sung by its star. Amazingly, the theme from Julie received an Academy Award nomination.

The first clue that this isn’t your average Doris Day picture is that the film is in back and white. It’s oddly disconcerting to see Day in anything less than vibrant Technicolor. Perhaps black and white was chosen to give the movie more atmosphere, if so, it didn’t work.

We find Day, as the title character Julie Benton, in the middle of an argument with her husband Lyle, played by Louis Jourdan. She gets behind the wheel of her convertible and berates him for his jealous outburst at their Pebble Beach country club.

“It’s unforgivable,” she scolds as she twists the steering wheel back and fourth, never once coming close to matching the moving scenery projected on the screen behind her. Suddenly, Lyle presses his foot down on the gas pedal, sending them on a wild and dangerous drive along the picturesque Monterey coastline. Julie tries desperately to control the car as they speed faster and faster, screeching along hairpin turns. Lyle finally brings the car to a stop and Julie runs for it, collapsing at a picture perfect spot overlooking the sea.

“I’m so sorry,” he begs, “So desperately sorry. Help me fight this thing. I was jealous, jealous, blindly jealous.”

“He nearly killed us both,” Day needlessly reiterates in a breathy voiceover, “He seemed so sorry, so desperately sorry.”

Later, in front of the fireplace of their beachfront home, they discuss the mysterious circumstances surrounding the suicide of Julie’s first husband. Lyle cannot stand to have any man, dead or alive, in Julie’s life. “I had to have more answers,” Day whispers.

The next day at the country club, she meets with Cliff (Barry Sullivan) her former brother-in-law. “Julie, did it ever occur to you that Bob’s neck could’ve been placed in that rope after he’d been strangled… by a murderer? Lyle was there that night wasn’t he?”

This presents poor Julie with a classic bad movie conundrum. Does he want to kiss me, or kill me?

Later, as Lyle tickles the ivories, Julie tells us that, “I’d listen by the hour to Lyle practicing.” Never mind the fact that we can clearly see she’s lying on the couch listening to her husband play. The constant voiceover narration in Julie is so wildly unnecessary that it borders on parody.

“But today there was something strangely disturbing about his music, a sort of savage fury that was almost frightening. Gradually, as I listened to him play,” she drones on, “I began evolving a plan.”

And what is her grand scheme?

“If Bob hadn’t died,” she asks in bed that night, “What would you have done? Would you have done it… killed him?”

Lyle admits to the crime. “I had to lie there in his arms, lie there in panic and wait for morning to come,” she tells us as waves crash meaningfully outside their bedroom window.

Come morning, she sends Lyle on an errand next door. Once again, though we can clearly see everything that she’s doing, Julie gives us a ridiculous play-by-play account of her desperate grab at freedom. Any normal person would simply make a run for it. Not our Julie. Though her window of opportunity is slim at best, she still takes the time to carefully pack the perfect traveling outfit and collect her make-up and toiletries from the bathroom counter.

“I had the urge to get out of that house and get out of it fast!”

Julie, perhaps a little less talk and a little more running for your life.

Lyle may be a murderous loony, but he’s no dummy. He removes a spark plug from her car, making escape by vehicle impossible. So, Julie must hitch a ride into town. She tries to call Cliff, but can see from the phone booth that Lyle has followed her. Julie evades him and makes her way to the Monterey police station. “Sergeant, I want to report a murder,” she cries.

Since her former husband’s case has been closed and she has no tangible proof of Lyle’s duplicitous nature, the police have very little to work with. When Lyle is questioned he denies everything. It’s a frustrating case of he said, she said and there is nothing the police can do. With Cliffs help, Julie checks into a San Francisco hotel under an assumed name.

It’s not long before she receives a telephone call in her room. “Julie. Julie, you’re going to die.”

“Lyle, you’re insane.”

The San Francisco PD can’t do much either, but they’re a touch more sensitive to Julie’s dilemma. “He admitted to killing my husband, he admits that he wants to kill me, and nobody can help me do anything,” she squeaks.

With two officers and Cliff standing guard, Julie tries to sleep, “I had the chilling sensation of being watched by Lyle. I could feel his presence. It was ominous. It was strangely disturbing.”

Julie is awakened in the night to the menacing notes of a tape recorder playing the same classical music that Lyle was rehearsing earlier. Desperate to remain free of Lyle’s psychotic clutches, Julie returns to her former profession as a flight attendant and stays with a fellow stewardess in her San Francisco apartment.

Meanwhile, Lyle follows Cliff home from work one night. At gunpoint, he forces Cliff to take him to Julie. Cliff leaps from the moving vehicle in a bold attempt to escape and protect Julie’s whereabouts. Lyle shoots Cliff, rummages through his pockets, and finds the address of the apartment where Julie is staying.

Though mortally wounded, Cliff stumbles to a farmhouse and finds help. He calls the police and they go to the apartment building to warn her. Julie is gone. She’s left for the airport, a last minute replacement on an outgoing commuter flight. Skulking in the shadows, Lyle watches Julie catch a cab to the airport terminal. He boards her flight and manages to keep his presence a secret by hiding his face behind a newspaper.

Midway through the flight, San Francisco homicide calls, worried that Lyle may have somehow learned of Julie’s location. The only way to know if he’s on board is for Julie to identify him. “Be casual,” the captain tells her, “everything depends on it.” She makes her way to the back of the cabin and then works her way forward, trying to remain inconspicuous and identify Lyle from behind. Sure enough, she recognizes the back of his brylcreamed head.

Considering that Julie wouldn’t shut up for the first half of the movie, this would seem to be a perfect moment for yet another long-winded dramatic voiceover, but now she’s inexplicably silent. As Julie makes a mad dash to the front of the plane, Lyle gains access to the cockpit. Unbelievably, a Wild West shootout ensues. The pilot is killed and Lyle is wounded. “I promised you it wouldn’t be easy,” he tells her, “You are going to be in this airplane, high in the air, with nobody to fly it.” With his dying breath he shoots the co-pilot.

A doctor on board proclaims the injury to be life threatening. There is only one person who can fly the plane. Guess who?

The co-pilot turns the plane around in hopes that the radio tower in San Francisco will be able to talk the plane down with Julie at the controls. He gives her a few pointers before passing out. On the ground, the macho guys at flight control give Julie instructions while constantly referring to her as “Honey.”

“I’m terrified,” she tells ground control as she brings the plane into its approach pattern. While wringing all the pathos she can out of the melodramatic scenario, she banks the plane left and then right with all the finesse of the driving skills she demonstrated earlier in the movie. Julie finally touches down… with her eyes closed!

With the plane safely on the ground, a look of relief passes over our heroines face. The orchestra swells and the screen fades to black. Not only has she saved herself and the passengers, but she has paved the way for heroic flight attendants in future bad movies about disaster-prone airliners.

In conclusion: The drama for the character she played on screen was no match for what Doris Day had to endure behind the scenes of Julie. In the book, Doris Day: Her Own Story, she admits that wasn’t particularly interested in making Julie. Both her previous husbands had been jealous of her success, so it’s easy to understand why Day would be reluctant to play a woman victimized by her husband’s psychotic jealousy. Day’s husband Martin Melcher, who also produced the picture, was finally able to talk her into taking the role.

During filming, Day experienced severe abdominal pain. Her husband insisted that she follow her Christian Science faith, forgo seeing a doctor, and adhere to the films strict shooting schedule. After the movie was completed, Day sought medical attention and found that she needed major surgery to remove an endometriotic tumor.

Despite all the turmoil, Day enjoyed shooting on location in Carmel so much that she later made the California coastal community her home.

At a time when most movies were still made on studio backlots and soundstages, the extensive use of location filming during Julie set it apart from other films of the time. Though real locations added authenticity to a film, studio sets were still considered easier to light and control. This may explain why shadows from the boom mike and camera crew can be seen in nearly every scene of the film.

Julie has all the ingredients necessary for a guaranteed bad movie classic. Take one part Sleeping with the Enemy (1991) and one part Airport 1975 (1974), add America’s sweetheart and you’ve got an overwrought, low-budget, woman-in-peril thriller that will satisfy any fan of cool cinema trash.